- Home

- Josh Barkan

Mexico Page 12

Mexico Read online

Page 12

“Jeremiah,” my father told me, after I had learned about the scheduling conflict, “if they want you to sit, sit. If they want you to shit on command, shit on command. If they want you to roll over, roll over.”

My father had been in the military for four years in Vietnam. Before he got his cancer, perhaps from all that Agent Orange over there, he told me, “The proudest thing I ever did was serve in the military. It made me into a man, out of a lazy sack of potatoes. It taught me order, discipline, and how to serve my country.” He said he had absolutely no problem shooting gooks as he was told. He said there were people who knew better than those of us at the bottom of the heap, and sometimes you should just listen to them. He said all that second-guessing about the wars in Vietnam, Iraq, and Afghanistan was done by a bunch of crybabies who needed to toughen up and take one for the team.

“All those liberals,” he said, “are always saying President Bush was fucking up, not showing the caskets of soldiers when they came home to Dover Air Force Base. Well what the hell do they expect him to do? Put those bodies on TV?” He was a big fan of Rush Limbaugh. If liberals said they wanted Hillary Clinton for prez, then they must want some kind of lesbian sex, he said, ’cause lord knows Bill wasn’t giving her any. He’d rant about Obama coming from some Muslim country like Indonesia. “And now he wants us to believe, after he’s tampered with his frickin’ birth certificate, that he’s not an alien.”

Under those circumstances, I was first a Cub Scout and then a Boy Scout. I worked my way up to Eagle Scout. In high school, I occasionally walked around the halls in my Boy Scout uniform with merit badges pinned to my sash. When my father would say some of those things, from Rush, it would disappoint me. I agreed with some of the things my father would say, but I’ve always been a stickler for facts. Facts are what win battles, I thought. Facts are what win wars.

I used to stay up at night, as a kid, reading Time-Life books my father had about the battles of Iwo Jima and the landing of our troops on D-Day. I was impressed by the way Eisenhower had planned for that invasion, not letting any of the enemy know about the buildup of Marine amphibious ships, and keeping everyone on a need-to-know basis. I memorized those signs from the books that said LOOSE LIPS MIGHT SINK SHIPS and CARELESS TALK COSTS LIVES. And one of the phrases I learned is that when you confront the enemy, and when you do something wrong in battle, you have to admit it to regain the mission.

What I’m getting at is that even though the army exonerated me for what happened six days before I finished my tour in Mexico, the record needs to be set straight. The chips have to fall where they may.

Charlie and I had done everything together for four years when the incident happened, April 26. Stateside, before going down to Mexico, we went through our ROTC training together. Some Marines say the training we get in army ROTC is cushy, but beyond the extra studying with books, and strategy sessions to be leaders—able to explain to the troops, clearly, what our mission is—we go through the same rope courses and rubbing of our faces in dirt. I remember, once, after carrying sixty-pound packs of rocks, running in the hot Kansas sun, with the atrociously humid heat of 114 degrees in the month of August, I was lagging behind Charlie pretty bad, a hundred feet back. We were supposed to be jogging together, as a group. There were thirteen in our training platoon. I was extra-dehydrated. I had failed to obey orders and to drink two quarts before we’d started running. We were out on the WSU golf course, next to the main university campus, and I saw the golfers hiding from the heat under their golf carts, getting out of the carts only to barely lob balls down the fairway. I was tempted to lie down on the patchy grass of the fairway. It was so hot, even the grass was dying. I wanted to sit and say, “This is it. I can’t go on. I can’t take it anymore.”

I had struggled through all the test-taking for years, with my dyslexia. The office of student services, on campus, had told me I had a right to take exams with twice the amount of time, and at first I, regrettably, requested that amount of time. But I told myself it was OK if it was necessary to complete the mission, and I slowly weaned myself off that extra time. I wanted to be a full soldier, complete and proud, just like everyone else, and I learned I could be. Usually I carried my pack, not only keeping up with the group but leading it, yet my legs cramped up bad this day. Charlie could have just left me there to sit on the grass, but he risked his standing in the eyes of the other soldiers—being seen as someone who had a friend that might be going soft—and came back and lifted me off the ground. He carried my pack in front, his in back, and let me hop next to him. We got back a full half hour late to the gym, where all the others were waiting. But Charlie insisted on carrying me to the end of training.

The soldier, Charlie, watched his buddy, Jeremiah, through binoculars at the Central de Abasto market. For five weeks they had been ordered to direct a sting operation at the market. The place was full of fish stalls, small vendors selling slabs of tuna, shrimp by the kilo, lobsters, oysters, cheap sardines, and tiny fish to cook up and fry in the inexpensive restaurants of Mexico City. The air stank of fish. The stalls were elevated on concrete platforms, where trucks came and unloaded their catch, trucked in from the Gulf Coast on ice. Hundreds of trucks arrived in the first light of dawn, an army that drove from the coast during the night, to bring fresh fish to the whole of the nation’s capital, Mexico City. It was precisely all the trucks that made it perfect for smuggling cocaine. Smuggling boats on the coast mingled with other fishing boats near Veracruz, and the trucks at the fish market were so full of blocks of ice and fish, there were a million places to hide kilo bricks of coke.

The Mexican authorities were corrupt, and Charlie had been bought off, too, but Jeremiah didn’t know anything about their corruption. The Mexican authorities pretended they hadn’t authorized the operation. They’d said, in front of Jeremiah, gringos should stick to the north where the action was. They insisted all the big cartels were operating and fighting in the north, along the border, or in Sinaloa along the Pacific Coast. It was well known that many of the Mexican authorities didn’t want to see what they didn’t want to see, so the cocaine, pot, and meth ended up passing through the border into the U.S. and coming by hidden rail cars and in small boats into Texas, or attached to tourists as they flew into New York. The ingenuity of the smugglers was never-ending. The drugs didn’t always come on small planes into the deserts of California or into Florida. They came in the bowels of mules, in latex bags in their intestines. They came in boxes stuffed into beehives, they came inside panels of old cars and in trucks as they went over the Mexican border. Everyone was a suspect, and Jeremiah had been trained, during his ROTC classes in Wichita, and then in his Special Forces training, to understand the enemy could be anywhere. So when the U.S. government gave the go-ahead for the sting operation, Jeremiah felt the mission must be getting close to some real drug-busting if the Mexican authorities wouldn’t authorize the mission. They must be cutting close to the bone.

Charlie watched as his longtime partner, his buddy Jeremiah, whom he’d gone to Special Operations Group training with, appeared in the distance with a briefcase of cash, to meet his counterpart, the drug dealer Francisco Sosa. Through the binoculars, seeing Sosa live for the first time, Charlie was impressed by Sosa’s formality. Often the drug dealers dressed in Hawaiian shirts that draped over their fat bellies, over slacks that fell to white alligator-skin shoes. The look was clichéd and gave them away. But Mr. Sosa wore a dark, worn-out suit and a frumpy panama hat, which made him look like he was the owner of a large area of fish stalls and truly from the coast, just as he was supposed to be. Through the binoculars, Charlie saw Jeremiah shake hands with Mr. Sosa. Sosa looked left and right, as if making sure no one was watching. He looked convinced the man with the briefcase meant business. He shook hands with Jeremiah again, and took him inside a fish stall.

Charlie watched the whole event from the inside of a fish truck with some dark windows and listening equipment, across the wide parking lot of the m

arket. The outside of the truck looked like a run-down Isuzu delivery truck, one of the miniature vehicles that plied the streets of Mexico City. He switched to an image inside the fish market where Jeremiah talked with Sosa, transmitted by a camera they had put in the market a week ago.

Sosa said, “I promise you the product is fresh and of the highest quality.” He never referred to the cocaine as coke, but always as “the product.” It was known this was the best way to avoid any recordings being used in court, though the judges were mostly bought down in Mexico.

“Can you give me a taste of it, now?” Jeremiah said.

“We can give you a taste of whatever you need. I assure you the product is fresh.”

Sosa told his assistants to bring some of the product. He looked around, to see if he was being followed into the back room of the fish-market stall. The image was clear. The head of a giant swordfish poked a long snout from behind Sosa, so the sword seemed to come out of his hat. Charlie zoomed the camera in on Sosa’s hands. There was a brick of the product, a kilo of white cocaine, wrapped in layers and layers of plastic with tape. Sosa cut open the block his assistants had brought him. The outside of the package was brown with dark red blood on top, from the guts of fish the package had been sent in. Sosa stuck in the tip of his penknife, with white mother-of-pearl on the handle, and cut at the dense white brick until a few pieces came off in his hands. He gave the brick to Jeremiah to hold, to feel the weight. He lifted the blade of his penknife up to Jeremiah’s face and gave the knife to Jeremiah. Jeremiah picked at the area Sosa had cut. He stuck his finger inside the brick and pulled it out with powder still clinging. He put the finger to his lip and tasted the powder and it numbed and tasted rich and real.

“My people will expect the shipment in three weeks,” Jeremiah said. “Two hundred bricks. No more, no less. On time. To Houston. You know the place. Everything you asked for is here.” He handed over the briefcase.

Sosa took the briefcase and handed it to his assistants. They took the briefcase to a different back room to count. They came back and told their jefe it was all clear. Sosa shook Jeremiah’s hand. “It’s a pleasure doing business with you.” Jeremiah left and kept walking. He took a taxi, as predetermined by the operation, to a safe house.

Charlie sat in the truck and gave a thumbs-up to three DEA and CIA officials in the vehicle. They slapped each other on the back. This was the first test to see if the shipment would work, to be sure they had the real guys. The next time, they would arrest Sosa. With the recordings, they could begin to nail Sosa in the States, or they’d take him out, if necessary, in Mexico.

Later that night, Charlie called his corrupt Mexican counterparts to tell them Jeremiah had delivered the money and that the product would be shipped to their contacts in Houston. It was a perfect scam. The money had come from the U.S. government. The U.S. government thought it was paying for the first phase of a real sting operation. Only next time, when they went in to make the final bust, Sosa mysteriously would not appear. He would be tipped off. Charlie would pocket a million and a half of the current six-million-dollar shipment to Houston, and then retire. Jeremiah had no clue he was being duped by his best friend.

This is how it happened. This is how you end up shooting your own buddy.

Three weeks before what they call the “incident” in the military report—which wasn’t an incident but a shootout clusterfuck—I went for drinks with Charlie. It was the day after the first Sosa connection. Charlie wanted to go drinking and whoring, and while I tended to avoid that kind of crap, to remain as upright a soldier as I could, after posing as the decoy with Sosa, which I had been selected for by picking straws with the other guys in the group, I felt I deserved some booze and pussy.

We started out having a martini at the Condesa DF hotel, a super-fancy place that always seemed out of my budget, where the pool on the roof shines aquamarine, in cool hues, up to the pulsating sky of el DF at night. There were fancy women who went to the hotel, women who wore designer dresses and who walked with imported Italian leather shoes, and me and Charlie sat in one of the white couches with a view of the skyline and of the hemlines of those women as they went by, and it felt like life was good, downing the vodka in shot after shot with a whole bottle Charlie insisted on buying.

“Ain’t this the life?” Charlie said. He was chewing on some ice, and he popped in a cocktail shrimp from a plate of twenty he had ordered. I thought of the simple bars of Wichita, where the women all look like aging sorority girls by the time they’re twenty-five, where the only plan is to get married, find a solid job, and raise the kids, if you don’t get caught up in a divorce too soon and they make you pay alimony.

“I’ve learned a thing or two over here,” Charlie said.

“Like what?” I said.

“I’ve learned black and white can be the same color, if you look at them long enough.”

“How’s that?” I said. I was into reading martial arts books and strategy by Sun Tzu about the art of war, and I understood how you could take the power of your enemy and absorb it to fight back at them, but I didn’t understand what he was getting at.

“Well, you know how here—if some Mexican says they’re coming to dinner, they may or may not come?”

“Yeah, I hate that,” I said.

“Well, at some point, I came to realize maybe I was the one with too rigid an expectation the person should come.”

“But they should,” I said. “Don’t give me that crap you’re going all culturally relative on me. I hate that relativism. Some things are right. Some things shouldn’t be done.”

“Okay, okay. Different example. Here, if I call some woman up on a date, and I go out with her and she doesn’t like the evening, then she tells me she had a good time. She smiles at me and says I’ll look forward to your call. She’s giving me the turn-on but she really means the turn-off.”

“What’s so good about that?” I said.

“Because no one has to do what they don’t want to. They just do what feels right and worry about everyone else’s feelings later.”

“It sounds like you haven’t thought that one fully through yet,” I said.

Charlie went over to the pool, where a woman in a long, silk dress with flowers printed on the fabric was standing alone. I watched him from my seat in the leather couch. “Hey, señorita,” Charlie said. “How about grabbing one of your woman friends and going out with me and my buddy?”

The woman smiled politely at Charlie, and looked down at her shoes.

“Aren’t you interested in going out with a handsome stud like me?”

Charlie looked as out of place in the hotel as if you had just dropped him out of an army helicopter onto the roof. He was handsome and tall, but his whole body language was stiff. He gestured too much. He waved his hands in the air, trying to persuade the woman she should go with him. He looked like a soldier trying to buy a camel in a foreign land, and these women weren’t camels.

“Excuse me,” the woman said to him. She was speaking in English, because Charlie had been speaking in English to her. None of us spoke much Spanish. “I would really like to be able to go out with you, sir, but I’m afraid I’m busy tonight.”

“Aren’t I good enough?” Charlie said. “Don’t I look good enough? Don’t I look like the kind of guy you would wanna bring back to your mamacita to show off?”

The woman winced. She was standing by the edge of the pool, next to a ladder that went in and out of the water, and she started to grip the ladder tightly like she needed something to help her out. She started to step away, trying to walk slowly so she wouldn’t seem impolite.

“Oh, now, don’t go away, little honey…” Charlie said. “Don’t you do that.”

One of the men a couple booths away, the manager—a tall Mexican wearing a tailored suit, with a black shirt made of silk and expensive leather shoes, a five o’clock shadow neatly cut in the way of the fashion of the day, and bald in a manly way—came over and said to Ch

arlie, “I’m sorry, sir, but it seems the woman isn’t interested.”

“ ’Cause she thinks she’s too rich or too fancy,” Charlie said, shaking his head. “That’s what they think, around here.” He said this turning back to me, but then, speaking so loud he was almost shouting it to the entire rooftop, continued, “It’s all about class, class, class in this fuckin’ country. Everyone thinks they were born from some rich Spanish king or queen. Like they’re all fucking güeros.” He was using the word for “whitey”—a güero. He was saying everyone wanted to be a whitey.

“I think it’s time to hold your liquor better, soldier,” I said to Charlie. “It’s time for you to get in line for roll call.”

“That’s your problem, Jeremiah. You’re always thinking the only path to take is the one of a soldier. There are other paths, too,” he said.

In the heat of the moment, I let the comment slide. I didn’t think all that much about what he was saying. I wanted to stop my buddy from getting into a fistfight in a fancy hotel with the other Mexican guy, before he called the bouncers.

“Come on, soldier,” I said. I pulled Charlie’s arm.

“She likes me. I’m telling you she likes me. Black is white. I’m telling you.”

By that time, the woman had moved quickly to the far side of the rooftop patio. The water from the pool cast strange shadows against everyone’s faces. I saw a darkness, and sneer, on Charlie’s face I had never seen quite the same way, though he often liked to get into bar fights. I knew the first rule we were taught about being in another country: Always learn the local traditions and culture. Get the other culture on your side. Use the strength of the enemy village and government to engage in counterinsurgency.

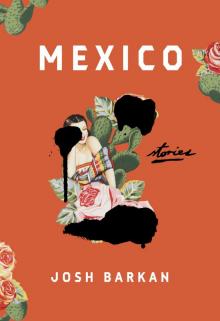

Mexico

Mexico