- Home

- Josh Barkan

Mexico Page 4

Mexico Read online

Page 4

But now, years later, I wondered if I had done wrong to separate his daughter from him forever.

“There are these two kids in my tenth-grade class,” I told Sara, “and today the father of one of them came to school and said they should break up, they shouldn’t be together.” I told her the rest of what had happened that day.

“How can you equate the kids of two rival narcos to us?” she said, at the end of what I told her.

“I’m not,” I said. “I know it’s different. But is there any real reason why the two of them should be kept apart, if they love each other, other than that their fathers hate each other?”

“You complicate your life,” Sara said. “Stay out of it. Let the fathers take care of it. Or, if you really feel like doing something—before you meddle with the two kids in your class, go visit my father and make things right.”

“Make things right? You know the fault was never mine. It was him.”

“It takes two to build a wall,” she said.

—

It was a windy, sunny day three weeks after José’s father had come into the classroom. The days were getting longer. Spring was in the air, even though the seasons don’t change all that much in Mexico City. But it felt like a spring day, with a gentle breeze and the sky bluer than usual, without the frequent pollution of Mexico City, and I stood in front of one of the small motels that litter the city, made for romantic affairs, usually between bosses and their secretaries, or between married men and their lovers. This motel was called Amor del Paraíso and was located near the Central de Abasto, a market where every kind of food is sold, and where all the restaurants of Mexico City come to buy their fish in the football field’s length of stalls.

I had parked my car a block away, after following Sandra and José riding in a small, black BMW that belonged to José. As they drove through town, I saw them lean into each other at the traffic stoplights, José kissing Sandra as she turned into him, and I could see him twist his head back, occasionally, to see if any of the security guards of his father were following, or the guards of Sandra’s family. He must have sensed someone was on his tail, but the mind sees what it is inclined to see, so he couldn’t imagine his teacher was following him.

I had listened to Sara, and also to José’s father when he’d spoken to the students in class. I separated José from Sandra, as far away as possible, placing him in the front right corner of the classroom, near the door where his father had peered through the window before telling me what to do with my class. It was embarrassing to move José. It meant admitting to everyone in the class that I wasn’t their leader: that I was a coward, that I would teach them the rights and wrongs of history and about great leaders like FDR but that in this class I wouldn’t practice what I would preach. It’s hard to talk about the women’s suffragist movement when you won’t even let a tenth-grade boy and girl, who love each other, sit next to one another.

Beyond separating them, I went and told the principal what had happened in the classroom. This was the ultimate cover-your-ass move. I hated reporting on Sandra and José. I hated reporting on José’s father, too. It went against every fiber in my body. But Sara had asked me to do this, and she was right that it was common sense. What if José’s father came back with guns? What if he became more violent? The administration had to know what was happening inside the classroom and to decide what to do next. The principal shook her head as I told her of the incident. She wiped her palms on her tight wool skirt and said she agreed José and Sandra should be separated in the classroom. We discussed the possibility of expelling both of them, because of the threat of violence in school, but we laughed at the very moment we said this. That may have been the right punishment, but you don’t play God with the cartels, you accommodate yourselves to them. For the same reason, no extra security was placed around the school. Everything was left as before, to imply nothing had happened, except the separation of José and Sandra in the classroom to comply with the father’s will.

That was the official response. The unofficial response was that I wanted to see what José and Sandra were up to. You could certainly call this voyeurism. It’s what it was. But I liked to think of it as chaperoning the two of them. I know it might sound insane—me, a defenseless teacher without any weapons, and the people who wanted to hurt Sandra and José, narcos with guns. Certainly, in class, I hadn’t found the strength to stand up and protect them. But it was precisely because I hadn’t been able to stand up to José’s father, so far, and because I felt such cowardice was wrong, that I fought to find the strength to try to take care of Sandra and José in private. Any teacher worth their salt feels the students in their class are there more than to learn; they’re there to grow safely into adulthood. A teacher is as much psychologist, protector, and nurturer as the teacher of a subject. This is why they have parent-teacher conferences. This is why they take care of the students at prom, to make sure they get home safe. This is why they spend their short lunch break trying to help the poor student who doesn’t have anyone else to speak to in class. In whatever limited way I could, I wanted to try to protect Sandra and José. If I could find a way to keep them safe from their parents, I became determined to do that. So, every day for three weeks, I followed them.

This was the fourth time in three weeks Sandra and José had come to this motel. The first time they’d come, I’d stood far in the distance, not approaching closer, waiting a couple of hours until I saw them exit the hidden curve of the motel’s in-and-out entrance. They were safe, still together, still unharmed, still undiscovered by their fathers, and I breathed a sigh of relief as they came out, José looking carefully left and right to make sure none of his father’s security guards were watching.

The second time, the man working at the check-in desk asked me if I needed anything, and I said I just wanted to know the rates of the place for future use. I was too scared to go any closer, and I left early, back to my home and to Sara.

The third time, I grew so bold as to walk into the area of parked cars until I found José’s car in front of one of the doors. I put my ear against the door, and I could hear them laughing with two friends, the four of them smoking pot. I heard the high laughs and rambunctious jumping on a bed of four teenagers goofing around. That was enough for me. I didn’t need to know more. But I kept following them, feeling like I was their guardian angel. If I had to castigate them, or separate them in public, at least I could protect them in private. I looked for ways they might be able to escape from the motel. I checked out where there were exits and what roads anyone who wanted to harm them would come from. If I knew the exits, maybe I could lead them to safety when the time came, alert them to get the hell out of the place before it was too late.

This fourth time, as I stood across the street waiting for José and Sandra to come out, I saw two black Cadillac SUVs approach from the right, down a one-way street that led to an on-ramp of the highway that passed in front of the innocuous motel. I couldn’t tell who the bodyguards inside the SUVs belonged to—Sandra’s or José’s family—but I knew they must have something to do with them. By now, I’d discovered there was a small rear entrance to the motel. It was made for the cleaning crews, so they could take laundry in and out. I’d had far too much time to explore the place—the bland beige paint that covered everywhere except the blue palm trees stenciled on the interior courtyard, where the cars were parked, and a red heart painted on the door to the check-in desk.

When I saw the SUVs approach, I ran across the street behind them as they pulled in front of the motel, and I hurried along the dying cacti and volcanic rocks littered with juice boxes, condoms, and other trash thrown along the side of the motel. A furniture construction warehouse, small and old, with sawdust flying to the ground toward the motel, ran along the path to the back, and I squeezed between the two buildings hearing the sound of a whirring table saw. It was the sound of wood being ripped in two for cheap pine furniture in poor homes. I reached the back door. It was jammed

for a second. I picked up a rock and smashed at the lock. The door wasn’t closed with a key, it was just stuck from loose hinges, causing it to lean sideways. When I came into the inner courtyard, I looked fast to see if José and Sandra were in their usual room, parked on the left, and they were. Across the thirty-yard courtyard, I could see the two black SUVs. The men had gotten out from the SUVs, and they were entering the check-in area to ask, no doubt, for the check-in book. I’d looked before, the second time I’d visited the place, to see if José was smart enough to use a fake name, and he was. At least he had no illusions that no one would come for them. It might take a couple minutes for the men to pry out of the man at the front desk where the two of them were staying. But it wouldn’t take longer, so I knew I had no time to waste.

For a moment, as I stood in front of their door—the cheap wood dry with the dust of the city, the unmistakable sounds of the two of them making love—I thought about turning and fleeing. What the hell was I doing here? What if I was wrong about the guys in the SUVs? What if the men dressed in black that came out of the SUVs wanted nothing to do with them? What if they were looking for someone else? There’s an edge, at the point of a knife, when you can fall to the side that gets cut or to the side left safely behind. But I didn’t waste time knocking when I found the door unlocked. I opened the door and saw José on top of Sandra.

Her hair was sweaty, spread to all sides. José looked at me and said, “Son of a bitch! What are you doing here? I’ll kill you.” He reached for a gun, beneath the bed. He was ready for what he knew was coming. I put my hands in the air and held them there. José stood up, his chest hairless, thighs firm from playing soccer, hair still held back from gel and from Sandra’s fingers combing through his hair. He was a naked man with a gun. Sandra tried to cover herself quickly with the blanket, but one of her legs strayed out from beneath the covers, and she could barely hide her breasts.

“What the fuck?” José said. “Mr. Jacobs. What the fuck? What are you doing here?” He was still holding the gun pointed at me, but he lowered the 9mm a little.

“You have no more than two minutes to get out of here,” I said. “There are security guards. Coming. Fast. At the check-in desk. You have two minutes to get out of here, at best, or they’re going to find you.”

“How do you know this?” Sandra said. “What are you talking about?”

“Get out the window, quick,” I said, pointing at the window that led to the pathway between the motel and the building where furniture was made. “Open it and get out now. Or come with me to the back entrance.”

“You’re crazy,” Sandra said. “If they’ve come this far they’re going to cover every way out. They’re not going to let us escape.”

José put his pistol down, threw on his jeans, and grabbed his pistol again. He ran barefoot, without a shirt, to the window and tried it, but it was locked. I told them we had to go. I told them we should run out the way I’d come. I waved at them to follow me, but José and Sandra wouldn’t listen. I ran back into the motel parking lot and hoped that if I led by example, they’d follow. I’d done as much as I could. I’d stuck my neck out way too far to stay around to see what would happen next. I ran to the back of the motel, farthest from the check-in desk, heading to the door I’d come in before. When I got to the back, I turned around and saw the men opening the glass door at the check-in desk, and I knew I didn’t have time to fully escape, so I hid behind a Coke vending machine.

I can only tell you what I heard next: the sound of men running with polished black shoes over the pavement. The sound of the men running up to the room where Sandra and José had been mating. The sound of glass breaking. Perhaps from a chair? José told Sandra he’d broken the window. He told her to go out before him. He must have had his arms behind Sandra, trying to push her out the window. The sound of a small gun firing, which must have been José shooting at the men running after them. The sound of the guards letting out round after round of their large pistols. The guards weren’t from José’s father. They were from Sandra’s. They shot José. “Come with us, you slut,” they yelled at Sandra. But she told them she’d rather die than leave José. “If you come any closer I’m going to kill myself,” she said, and she must have found a pistol, because there was one more gunshot and then she didn’t make any more noises.

—

A week after the death of Sandra and José, I was in Polanco, in the evening. It was Friday night and I saw the Jewish men dressed in their black fedora hats, heading to temple. I had walked in the Parque Lincoln earlier in the evening, with Sara, after school. I felt I needed to be back in the park where we used to stroll. I needed the calm order of the tall palm trees that spread over the park, protecting the walkers below like umbrellas. After the shooting of Sandra and José, I had told Sara immediately what had happened and where I was at the time of the shooting. I had even confessed to her I had been following Sandra and José for three weeks.

“You crazy, irrational man,” she said, but then she held me tight, stroked my head, and let me know she loved me as much as ever. By her fingertips, I could tell it was precisely the fact I cared so much about Sandra and José that had moved her to give me comfort, and to marry me in the first place.

As we walked in the Parque Lincoln, and I saw some of the Jewish men gathering to go to the synagogue, I said to Sara, “Why don’t we go to temple? Why don’t we find your father and tell him we’re sorry he’s so far apart from us?”

Sara looked at me sternly. She gave me a look that said it was better not to stir up old wounds. What she actually said was, “But you don’t believe in God.”

“Well, I don’t,” I said. “If ever I needed proof of the absence of God, look at what happened to Sandra and José.”

“That’s not proof of anything,” Sara said. “That’s proof bad things can happen to good people, or to people who don’t deserve what they get. But that’s proof of nothing. Besides, you can’t prove whether God exists or not. That’s why they call it faith.”

“Why should your father care whether I believe in God or not?” I said. “Isn’t it enough I’m proud to be Jewish? Isn’t it enough I try to live my life in a good way?”

“For me, it doesn’t matter,” Sara said. “For me, I can see your intentions are good, and that’s close enough to God for me. But for him, God is God and you’ve betrayed his faith.”

“I’d like to go to temple and find him,” I said. “I don’t want us to live the rest of our lives feeling he has disowned you because of me. I’m not comfortable with that burden.” Following Sandra and José’s death, I felt a need to go to the temple to find him.

Sara relented, after we had a few more rounds discussing the futility of seeking her father out. I saw a man with a black fedora, black pants, and shiny shoes, walking down the Calle Goldsmith toward Avenida Horacio, and I decided to follow him. Sara followed with me, though I could feel her lagging half a step behind, the weight of her resistance wanting to pull me back to the park. There was no need to follow the man; we knew, of course, exactly where we were going. There was no doubt where the temple was where Sara’s father would be walking to this very moment, and who knew if this other gentleman was going to the same temple or to another? We walked together in silence for ten minutes, and then came to the imposing door of the temple with Hebrew letters written above the door.

“I’ll wait outside,” Sara said. “I’m not dressed properly to go in.”

“Please,” I begged her. “Do this for me. For us. With a gesture we can repair things. You were the one who told me a wall is built by two people, not by one.”

“You go in first,” she said.

I paused in front of the long handle, feeling the weight of the door, the weight of the thousands of years of tradition the temple represented. But I am a man of faith, too, I thought, even if I don’t believe in God. I am a man of faith in the brotherhood of all men, and I belong to my tradition as much as Sara’s father, I thought.

When I came into the temple the men were already grouped below on the bottom floor, davening, listening to the rabbi lead the prayers and reciting to him their responses to his calls. The women were upstairs in the temple. I saw Sara walk behind me, and then upstairs to the section for women, as I went inside the main temple area, below, to find her father.

There he was on the right-hand side, in back, as I remembered his place had been eight years before. It was as if he had stood in the exact same spot, praying, the whole time. His beard was now fully gray and his yarmulke sat sternly on his head like an anvil. I didn’t want to surprise him too much, by coming up from behind, so I chose to enter his bench row from the center left, where he could see me for a while as I came closer to him. The wood of the long bench, as I moved sideways toward him, was worn smooth from generations of congregants coming every day to pray, especially every Sabbath. When I came close to him, I could see his eyes wander left and he seemed to see me. But he showed no immediate expression. He continued praying, looking at the book with Hebrew lettering in his hand, and calling out in response to the rabbi. It was as if I weren’t there, as if an iceberg had come close to his ship, the Titanic, and he refused to acknowledge any ice. His ship was impenetrable, a fortress, impregnable. I came closer and closer, and was close enough that I could easily reach out to his hand to touch it. But still he made no motion to acknowledge me. It was now or never. I could leave this second with things as they were. I could leave with the same wall of silence between him and me and his daughter that had lasted eight years. For a moment, I considered moving back to the left, sidling into the center of the temple, and leaving. But the thought of Sandra and José came to me, the sound of Sandra shooting herself, and I whispered into the old man’s ears, “Your daughter loves you and would like to talk to you. And I love you, too.”

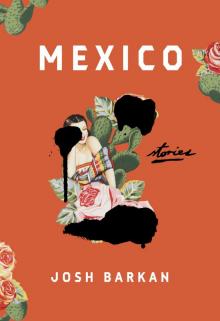

Mexico

Mexico